For the last few years, the idea that “Smart Cities” were the inevitable next stage in the evolution of urban spaces has been the consensus among policy buffs. It stands to reason: city-based clusters are where creativity and innovation have always flourished, because of the collision and co-operation between diverse viewpoints and diverse backgrounds of densely-packed residents.

In fact, chance meetings of people with different interests (sometimes called water-cooler conversations) were encouraged in some of the most innovative places in the world. I worked at Bell Labs, arguably then the most intellectually stimulating environment anywhere, and the deliberately long corridors to the cafeteria meant physicists, material scientists, electrical engineers, mathematicians and so on rubbed shoulders. The long-running games of Go in the cafeteria also encouraged random encounters among kibitzers.

When you added Big Data and Machine Learning into the mix, it sounded logical that a heavily networked Smart City would be increasingly efficient, and could be optimized for smart mobility, zero carbon emissions, resilience, digital transformation, and so on. All this is quite true.

But this vision struck me, as an observer at the UNESCO Netexplo Smart Cities Forum 2019, as overly skewed towards developed nations, as well as soul-less and clinical. From the point of view of a resident like me of a mid-sized city in a developing nation, these objectives were not very relevant to the issues that we faced, which are more elemental and basic:

the preservation of heritage buildings and water bodies

providing drinking water, reliable electricity and internet access

hygienic waste management and recycling/upcycling

the husbanding of animal and bird populations

managing marginalized populations of migrants and the indigent

disaster mitigation and recovery

and the provision of traditional public transport such as buses and metros.

So it was not a great surprise to me that Smart Cities failed the “crash test” provided without warning by the Wuhan Coronavirus pandemic, as described by Bernard Cathelat1, eminent sociologist. Says he, further:

Reading the conclusions of a CEPESS (Economic and Social Studies Centre) symposium (held in November 2016 in Louvain), we encountered the pioneering concept of ville réliante, which we borrowed to develop and model as Linking Cities.

“Smart cities bring a technological dimension to sustainable cities associated with innovation and digital solutions [...] But in our opinion, Eco-cities and smart cities do not sufficiently take into account human, cultural and political dimensions [...] The CEPESS wishes to make its contribution by proposing a new vision of the city, that of connecting cities, of linking cities: a model which places the development of links at the heart of the urban project.” (Jérémy Dagnies and Antoine de Borman, CEPESS.)

Furthemore, Cathelat (ibid, pg. 10) summarizes what might make a city more human-scale:

more vegetation

reduced concentration and decentralization

the stimulation of social interaction… and solidarity initiatives

more interactive governance.

In other words, a departure from the Cartesian, mechanistic point of view, and a call to a more humane perspective. I have written about the inadequacy of Cartesian thought2 and especially about the issue of emergent intelligence3 that arises from social interactions. We do need a more holistic perspective.

What did surprise me upon listening in detail to Bernard Cathelet’s excellent presentation in April 2021 was that I had encountered in my own village and small-city life elements of what he described as Linking Cities: a human rather than a technology focus, which make them more responsive/resilient to shocks. Somehow, I had overlooked them, in the headlong rush towards ‘modernity’.

Earlier, I had presented, at the conference on Disaster-Resilient Smart Cities at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi in 2019, a case study of the Smart Cities project where I live, Trivandrum, in southwestern India. It is a Tier-2 city with a population of about 2.5 million, the capital of coastal Kerala State, blessed with natural beauty and centered around an 1,800 year old Hindu temple, a grand historical monument.

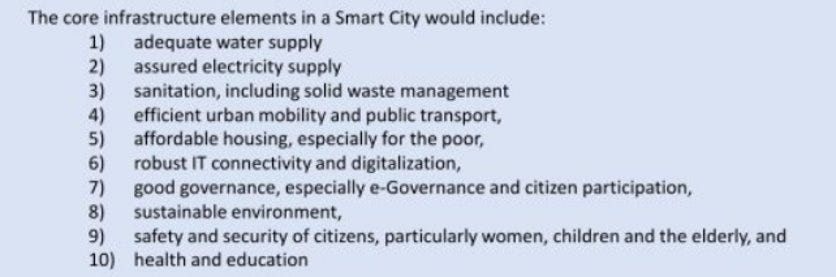

The official Smart City Trivandrum list of objectives is as follows:

This bears little resemblance to the futuristic utopian vision typical of a Western Smart City. Furthermore, developing nation cities cannot afford the investments needed to get to the Western level. Surely their citizenry would protest at what they considered frivolous, ivory-tower expenditure while their real, day-to-day needs were not being met.

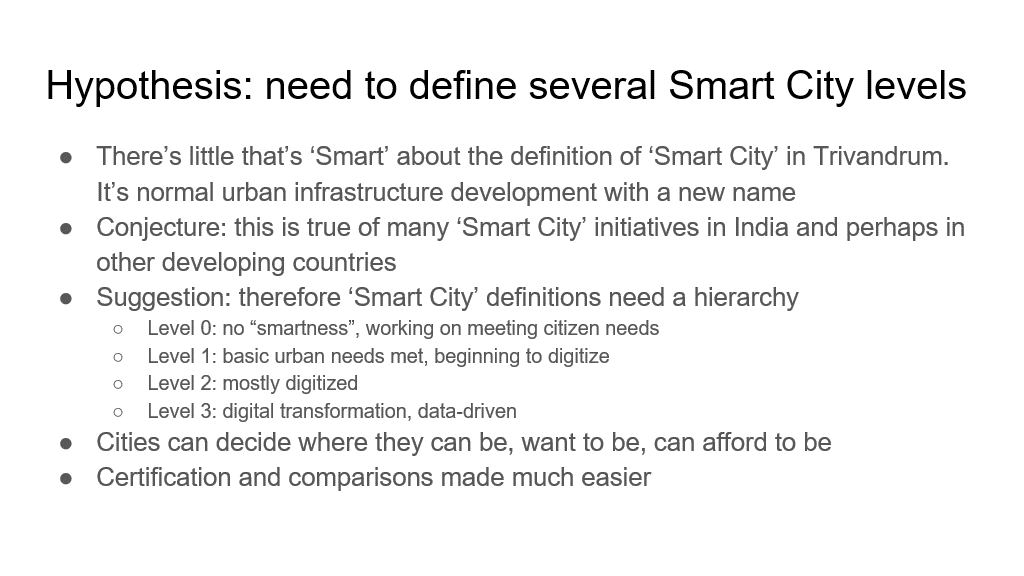

My conclusion was that cities evolved to be Smart Cities, and it was not one-size-fits-all. This distinction has to be recognized, and a simple way would be to acknowledge that there were several levels to which a city could aspire, and be certified. The analog I used was the Capability Maturity Model (CMM) for software developers, which has several levels.

I thought a typical developing country city should aspire to Level 0 first, which would meet the basic needs of its citizens; once that had been achieved, it could move up to the next levels.

What the 2021 definition of Linking Cities has given me, though, is a greater appreciation for the many things that my city and my village have (or had), which would handily allow them to be much better Linking Cities. In other words, we have, in the recent past, lost many good things, and pushed ourselves into urban dystopias in the single-minded pursuit of economic growth.

“Prosperity comes with three terminal diseases: debt, obesity, and tourism”: according to public intellectual Nassim Nicholas Taleb, in Bed of Procrustes. To that, one could add, ‘anonymity’ and ‘modernity’. I can remember in my own lifetime how there were working farms and paddy fields within a mile of any point in Trivandrum; instead of high-rise apartment buildings, most of the pleasantly undulating city had neighborhoods of single-family homes.

Linking Cities: Social Interaction and Solidarity

I grew up in a cul-de-sac of about 20 homes (new ones were built over time), and every one of them had a small yard and a profusion of trees and vegetable gardens. Over time, the plot sizes grew smaller (initially most of them were 6 to 10 cents (ie. 6%-10% of an acre), later they were as small as 3 cents, more crowded and cheek-by-jowl with the neighbors. Some homes were turned into rentals, one tenant on each of two floors (there is only one three-floored structure, which is three flats).

There was a community; it had a Residents’ Association, and every month the secretary would visit every house to collect the small dues, and that was an occasion to discuss any concerns the residents had. If there were major issues, a petition would be drafted and submitted to be municipal authorities. So there was a measure of self-governance and a sense of togetherness.

Periodically, there were get-togethers on somebody’s rooftop terrace or yard, where children would demonstrate their skills at song or dance; a guest might deliver a lecture on household finance or the medical problems of women. Everybody knew everybody else, including the transient renters.

In this enclave, only one household had a car; another household had a phone. All of us gave that single phone number to our friends and relatives in case of emergency, and it was a chore for the poor man with the phone to despatch his kids to the neighbors’ houses whenever someone called.

In the evenings, the children would gather on the street and play cricket or run around in the vacant lots. A particular favorite was the haystack that would appear after the paddy harvest: it was a pleasure to inhale the fragrance and feel the rough rice-stalks on one’s face. Periodically a few wild rhesus monkeys from the nearby large Palace compound would traverse the tree-tops and wreak havoc on houses with unguarded windows, or on the fruit-bearing mango or coconut trees.

The women would chat over their walls with their neighbors until it was dusk, and thus time to prepare the evening meal. Empathy and conviviality. There was no TV (literally), and this was their best form of entertainment.

All this has changed now. Every house has a couple of cars; every individual has a mobile phone. The children are busy with their tablets; the men with their social media or cricket. Women watch soap-operas on broadcast TV, or Netflix or Amazon Prime. People know each other vaguely, but there is no intimacy or sense of community; everyone is wrapped up in their own little cocoons.

Another aspect of urban blight is plastic waste. We simply didn’t have packaging when I was a child. Instead of cereals or vegetables packed in plastic in a supermarket, in the old-fashioned bazaar or corner grocery store they used to wrap up our purchases of lentils or tomatoes in old newspaper cones or pages ripped out of school exercise books. Meat was packed in banana or other leaves. Everything was biodegradable.

Even the unglazed clay cups used to serve tea in trains were biodegradable: tossed out on the tracks, they degraded into mud shortly.

Today our roadsides and especially railroad tracks are covered with plastic waste. Even worse, so are our urban water bodies: people unthinkingly throw trash into water, resulting in the gumming up of streams into fetid, disgusting pools which then overflow during the monsoons onto the streets. Plastic packaging is a curse, and whenever I segregate garbage, I am astonished at how much of it I have to haul to the recycler.

And there is no guarantee that any of this is recycled. Given the unscrupulous nature of petty traders and corruption in local government, it is entirely possible that the waste that I have laboriously sorted is just dumped into some hole in the ground, to leach everything from heavy metals to other toxic waste into the groundwater.

Without being mistily romantic about a past fifty years ago that definitely had its share of human suffering and environmental degradation, it is worth considering the hugely negative effects of the hydrocarbon economy: in climate change, in the proliferation of plastics, and the health effects.

Earlier, the newspaper boy, the milkman, the postman, and the fish vendor, among others, used to ride their bicycles, with their goods strapped to the ‘carrier’. Today, every one of them uses mechanized transport, either a two-wheeler or a three-wheeler. It is likely that their health has suffered from the reduced exercise.

There was ‘smart transportation’ then too, of a different sort. The produce from distant suburbs used to come by bullock cart: convoys would unhurriedly travel through the night, with the tinkle of a bell and a circle of light from their hurricane lamps. The bullocks knew the way, and the drivers would nod off. Now there are mini-trucks, often with loud two-stroke engines, that do the job: the bullocks are gone. They are no longer in much use in paddy fields, either.

Linking Cities: Vegetation

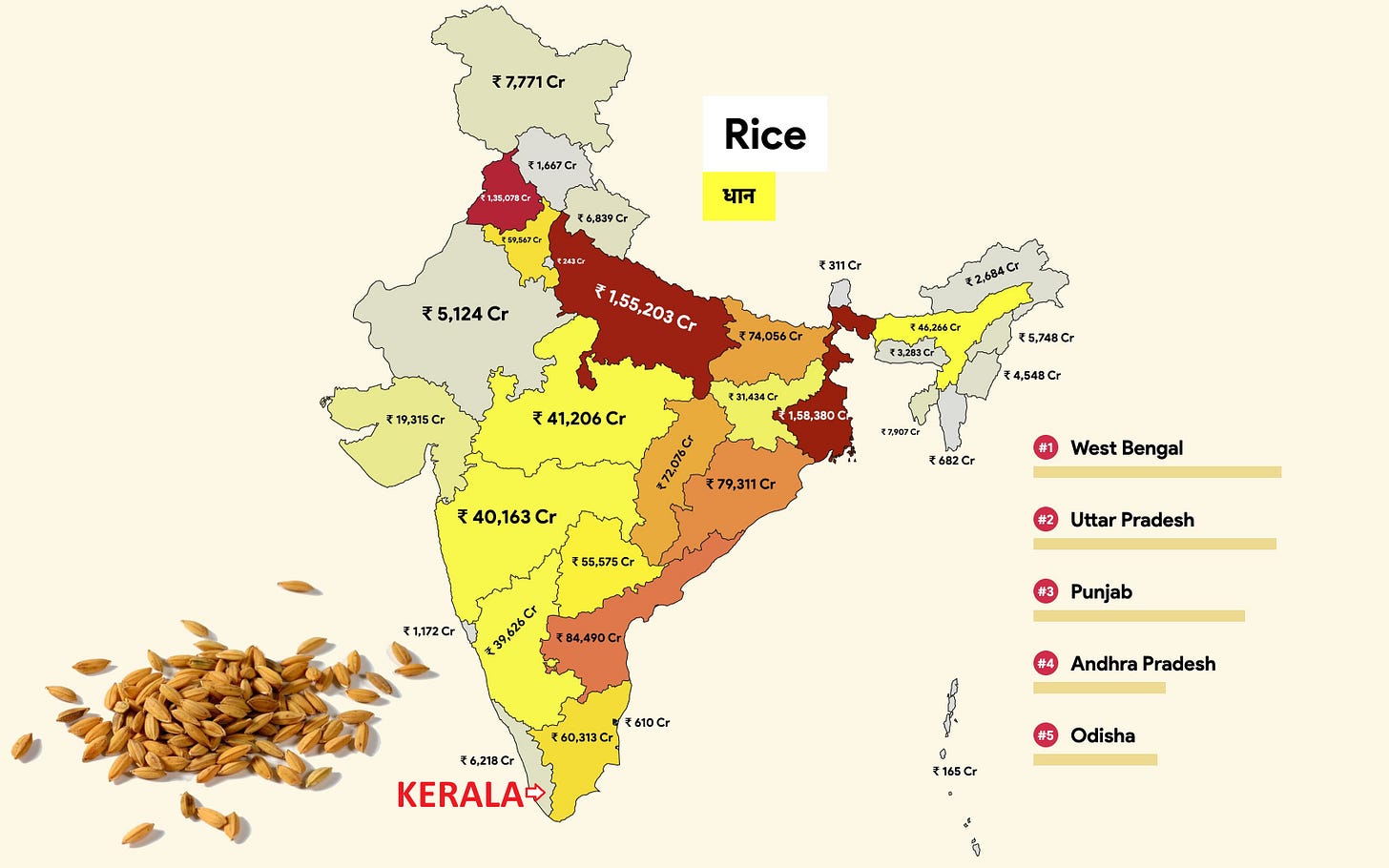

In fact, the paddy fields are gone, too. Every one of them within city limits has been paved over and turned into residential land, as demand soared with migration. In addition, well-meaning but highly damaging economic policies under left-leaning governments destroyed the very rationale for paddy cultivation. This is a warning for overly intrusive governments as in the San Francisco Bay Area: you can easily drive business away, as is already happening.

When I was a child, my great-uncle made good money from farming a few acres of land in our home village about two hours away. Later, my uncle, who was an agricultural scientist, made decent money running his father’s fields that surrounded his beautiful house with an interior courtyard open to the heavens. But over time, he told me, he was forced to subsidize his rice cultivation with his salary as a scientist. So he stopped farming; and others had similar stories.

Governments, with the intention of improving the incomes of agricultural laborers, pushed up minimum wages to the point it simply became uneconomical. Labor militancy meant that mechanisation was also not possible. Paradoxically, the end result was not that laborers got good wages: it was that agriculture disappeared. The laborers ended up migrating, and coincidentally, there was the post-1973 Persian Gulf oil boom: they became, in effect, slaves there with virtually no rights, toiling away in the blazing desert heat.

Well-meaning Western commentators were impressed by the high quality of life in our villages4 but their extrapolations5 may not have anticipated the downsides of “radical reform as development” as they put it. The delicate equilibrium that had sustained some of the best, well-watered, fertile, rice-growing land in the world for millennia came to an abrupt end in the 20th century.

The idea in Linking Cities of bringing vegetation and urban farming to cities, albeit with vertical farms or hydroponics, is appealing, because there’s something very old and deep in the human psyche that responds to crops, economics aside.

There are two other aspects of village life in Kerala worth noting: community and health.

Linking Cities: Family-centric Communities

There has traditionally been a matrilineal system of inheritance in the area among Hindus (though not among Christians or Muslims). Descent was through the women, and therefore property also passed down the female side, and a child belonged to one’s mother’s family, not father’s. The sisters in a family would live together in a joint family, and that would be matriarchal as well: women gained power as they aged. The husband moved in with the wife’s joint family.

This construct was particularly suited to an agrarian setup, because it ensured that landholdings remained intact with the joint family, and were not atomized through nuclear families splitting away. It was an economically sensible protocol, and women in Kerala were more equal than their sisters elsewhere in the country: they had economic freedom, and were not dependent on their husbands.

My late mother, a professor, remembered with fondness the joint family she grew up in: there was always some aunt to take care of the children even if the parents were busy; and the old people in the household had children to spoil and pass on religious and cultural values to. Somehow, everybody was fed and taken care of. My mother was essentially an orphan, as her mother died young and her father had a traveling job, but she, too, was brought up by the family.

Unfortunately, this system broke down when people started moving to the towns in search of non-agricultural jobs, thus setting up nuclear families of their own. Worse, in misguided zeal for ‘reform’, the princely state in the 1920s — possibly influenced by British prejudice, as about half of India was colonized by Britain at the time — abolished the matrilineal joint family.

As Nobel laureate Mohammed Yunus of the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh has demonstrated, women are far more careful and sensible users of money for the welfare of their families than men are. Men, on average, spend a large portion of their earnings on themselves, including in gambling, drinking and other vices.

This phenomenon is widely seen to this day. Every maid-servant in Trivandrum has the same story: they take an hour-long bus trip from the exurbs, and work for 2-3 hours cooking, cleaning, and washing clothes for middle class families. They might do this for two or three families, perhaps visiting them twice a week. It is a hard life, but it is one way to earn a living.

Every one of them complains about their lazy, no-good husbands, and often, alas, their layabout sons, who are casual day laborers or workers without steady jobs, and it is up to the women to maintain the household.

The woman-led joint family is far removed from single-mother-led nuclear families, and the sense of community and loyalty it engenders may have lessons for a world in which atomization, angst and anomie are major problems. How can that sense of togetherness be re-created?

Linking Cities: Decentralization

One of the consequences of the pandemic has been the increasingly tenuous links between geography and work. It turns out you can work — at least a lot of things can be done — remotely from anywhere. This is likely to be a lasting change. There are those who view this as an opportunity. For instance, there’s self-made technology billionaire Sridhar Vembu6, CEO of Zoho, sitting on a verandah (thinnai in Tamil) in a small village, from where he directs his global business.

This trend is likely to become more widespread, as ‘digital nomads’ build up their ‘network states’, as articulated in a wide-ranging podcast by Balaji Srinivasan7, a respected Silicon Valley venture capitalist, who himself has migrated to Singapore and India, reasoning that the future of technology will be in Asia.

Similarly, a number of technology workers have moved from the crowded Silicon Valley, to Austin, TX, or Miami, FL, to remote Montana or Colorado where they could enjoy nature, or to places like Estonia or Bali.

This, then, is the competition for Linking Cities: the good life is no longer confined to certain parts of rich countries. The truly global worker is now (almost) a reality. The age of decentralization is here; distributed systems, more robust and resilient, can now become part of de-globalization, and paired with blockchain and perhaps cryptocurrencies, can create an alternative model.

Linking Cities: Health

Finally, on to health. The pandemic has shown the limitations of technological solutions of monitoring or surveilling the population. Track-and-trace systems, including the vaunted Apple/Google cooperative venture, did not prove up to the task of predicting, isolating, or directing resources to the worst-hit areas.

Says Bernard Cathelat (ibid, pg. 40):

“Smarter city” professionals have to look at the issue of the balance between the cold logic and phenomenal computational ability of artificial intelligence, and another type of intelligence, a human one, whose talents lie more in the “right brain” of intuition, imagination, creativity and improvisation.

There is more. We may be reaching the limits of industrial medicine. Once again, the mechanistic Cartesian vanity of Western Science is reflected in the elaborate and expensive paraphernalia of the drug industry, although fundamentally its output is stochastic and not deterministic. There is only a certain probability of a medicine working on a particular person, and the gold standard, the Randomized Controlled Trial, is purely about correlation, and not about causation.

There simply isn’t a Theory of Disease in Western medicine, or, as it is called in India, allopathy. Whereas traditional Indian medicine, Ayurveda, does have a theory of disease, which is about the balance among three doshas: vata, pitta and kapha. When an individual loses the natural equilibrium amongst these, diseases emerge; thus Ayurveda has a causal effect for systemic, long-term illnesses, and a physician provides customized health care that is unique to the individual.

There is evidence, for example from the gut biome, that it is the disturbance of a balance (in this case between benign bacteria and malign bacteria) that causes much diseases.

An Ayurvedic physician spends time with a patient, understanding his family history, his work stress, his food habits and his hobbies, because all that goes into a gestalt of what he is all about. The physician then prescribes a treatment which includes herbal medicines, diet restrictions, yoga and meditation. Sometimes all that the patient needs is a two-week course of rejuvenation.

Can technology help in this personalized medicine? Of course, it can. An AI that can sift the Big Data about the individual and correlate his actions to his personality can help guide the physician. Tracking the effects of the course of treatment over time can also help.

But most of all, what can help is that there is a system of medicine that treats you as a human being with emotions and a certain personal history, rather than a Cartesian machine. Ayurveda has dealt with pandemics in its millennia-old history, and baked into its protocols are insights on how to improve immunity to fend off pathogens. Unfortunately, in the mad rush towards vaccines and anti-viral drugs, even the Indian Government has paid little heed to Ayurvedic formulations, even those that have shown efficacy against the SARS-COV-2 virus.

To sum it up, Linking Cities can indeed provide for better diagnostics and better healthcare especially if it takes into consideration traditional knowledge in medicine.

Nobel laureate Octavio Paz once said of his country, Mexico, that it was “condemned to modernize”. Linking Cities suggests that there doesn’t need to be either-or. You can modernize, but also retain that which is valuable from the past. Japan, for instance, has modernized without losing its core values. Linking Cities give us hope that we can, globally, do the same. Those who manage them have to think deeply about the Ethics of Linking Cities, and ask “Whose cities are these?”

April 19, 2021

Bernard Cathelat, “From Smart Cities to Linking Cities”, UNESCO/Netexplo Observatory, Paris, April 15, 2021, pg. 9

Rajeev Srinivasan, “Taking To New Technology May Be Nice But Not As Wise”, Swarajya Magazine, May 4, 2017 https://swarajyamag.com/magazine/taking-to-new-technology-may-be-nice-but-not-as-wise

Rajeev Srinivasan, “Going Beyond Data – On Intuition, Knowledge And The Connectedness Of Things”, Swarajya Magazine, Aug 3, 2017 https://swarajyamag.com/magazine/-going-beyond-data-on-intuition-knowledge-and-the-connectedness-of-things

Bill McKibben, “The Enigma of Kerala”, Utne Magazine, Mar-Apr 1996, pp. 103-112 https://www.utne.com/community/theenigmaofkerala

Richard Franke and Barbara Chasin, “Kerala: Development Through Radical Reform”, Promilla & Co, New Delhi, 1992

Financial Express, “Zoho’s Sridhar Vembu gives growth mantra to SMBs; suggests entrepreneurs to focus on rural India”, April 18, 2021 https://www.financialexpress.com/industry/sme/msme-eodb-zohos-sridhar-vembu-gives-growth-mantra-to-smbs-suggests-entrepreneurs-to-focus-on-rural-india/2235624/

Balaji Srinivasan, wide-ranging interview with Tim Ferriss, Episode #506, Mar 25, 2021, transcript and podcast at https://tim.blog/2021/03/25/balaji-srinivasan-transcript/

Share this post