Life vs. Livelihood: the #WuhanCoronaVirus Dilemma

Lives vs. livelihoods in the time of the Wuhan Coronavirus

Rajeev Srinivasan

On April 14th, the prime minister told us that the Wuhan CoronaVirus-related lockdown will continue till May 3rd, subject to certain loosening of restrictions to be announced by April 20th on a case by case basis.

The PM has a very difficult set of choices, and needs to juggle many issues. There are three important considerations, in order:

Lives

Food

Economy or livelihood

It’s an incredibly tough call. If you are lucky, all three can be managed. If not, the failures will be catastrophic. It’s likely that it is only possible to optimize any two; you cannot optimize all three simultaneously. But this is what resilience is all about: how can we manage the entire problem?

So far, we have concentrated on saving lives. That is not true of other countries, say the US, which arguably favored the economy over lives, figuring that there would be a certain number of casualties, as in the 50,000 deaths per year from the common flu. There the argument (which has taken on a Trump-centric culture war flavor) is over whether to dilute the lockdown.

It is almost self-evident that lives must be India’s first priority, because in a country like ours, with a creaking medical system and poorly regulated infrastructure, a pandemic could wreak total havoc. There was frightening talk of 500 million deaths.

That particular number came from someone soon unmasked as a person with a conflict of interest because he represents a company with test kits to sell, but practically the entire Western media was just waiting for a huge calamity, with Indians dropping dead on the streets in lakhs. They are startled, and find it hard to accept that there are only 500 or so deaths.

For a long time, data providers such as ourworldindata.org (https://ourworldindata.org/the-covid-19-pandemic-slide-deck) only published country-specific numbers of cases or deaths, whereas a more accurate metric for comparison would be cases/million and deaths/million. They recently started publishing this, and so has the Financial Times.

This data shows that India has done relatively well so far, which is nothing short of miraculous, and things can still go horribly wrong. At the moment, even though India’s first cases were observed as early as the end of January, that is 80 days ago, there has not been a catastrophic growth in either cases or deaths, although they are doubling every five to six days now.

How this was achieved is not entirely clear, and it probably has to do with both a) natural endowments of the country, and b) government interventions. Since so much is not known about the virus, it is so far unclear whether Indian weather (hot) or cuisine (spicy especially with turmeric and other known immunity-enhancing agents) or genes are at play.

It could also be the BCG vaccination against tuberculosis that we took as children. Nobody knows for sure. But the general exposure to pathogens because of weather, dirt, and squalor probably provides a certain level of immunity.

On the other hand, the government did take early steps, closing off China-origin travel, then international travel of all kinds, and finally the lockdown from March 24th. The resultant distancing from disease carriers surely helped flatten the curve, despite incidents like Delhi dumping migrant laborers on its borders, and the Tablighi Jamat event.

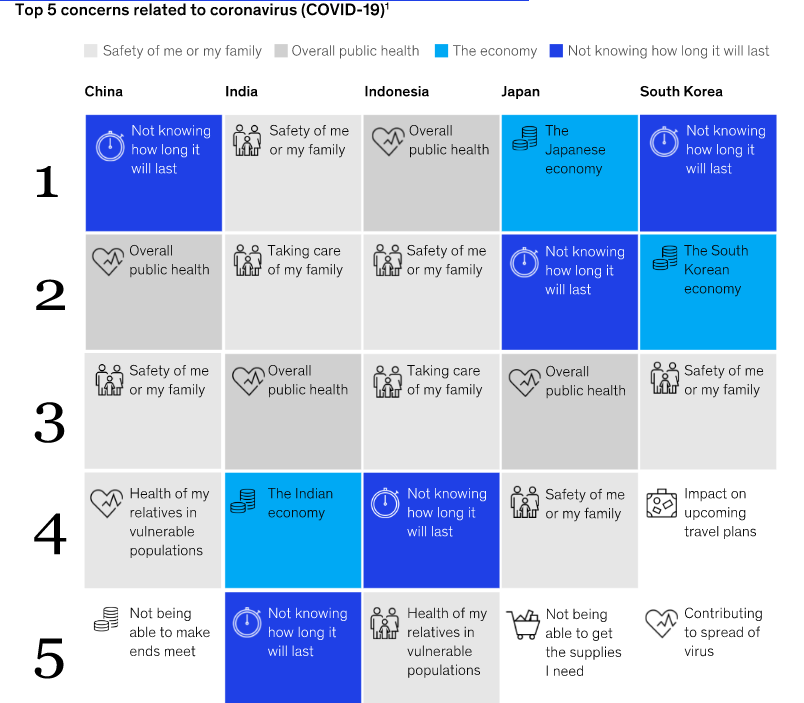

A McKinsey survey of consumer confidence in Asia from March 30th https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/asia-pacific/survey-asian-consumer-sentiment-during-the-covid-19-crisis?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hlkid=d222de540c0a4786bedbba46f3f1c0d6&hctky=1873873&hdpid=560ddc95-a00e-4648-a04a-c25075ace5e0 shows Indians are surprisingly optimistic about the impact of the virus: 52% of Indians think things will improve in 2-3 months, compared to 6% in Japan and 25% in South Korea.

Indians are also more concerned about their lives rather than their livelihoods, according to this survey’s findings. Incidentally, the medical focus may shift from the Wuhan Coronavirus shortly, as the monsoon is approaching, and recent endemic diseases like dengue and chikungunya may become the source of more deaths and hospitalizations.

But these results (assuming the survey is methodologically impeccable) hide two major assumptions: that there will be enough food to eat, and that people will be consuming (other) things. Neither is a given.

On the food front, it is clear that the stringent lockdown has affected the supply chain, which is unnecessarily long at the best of times. Too many intermediaries, all of whom need their profits. The net result is that the actual producer gets almost nothing for agricultural products, which also all ripen at exactly the same time, thus driving prices further down.

There are no facilities either for storage of produce (as in grain elevators in the US) or for value addition, as in turning tomatoes into ketchup. This means farmers may face ruin. As an example, there was a tweet about a farmer in Kasargod, Kerala who had 14 metric tons of ash gourd he had harvested. Fortunately the Horticorp responded to his SOS.

Food security has to be the highest priority now that there is a certain flattening of the disease curve. Apparently government-procured staples like rice and wheat are available in warehouses in substantial quantities, so that it is possible to provide free or subsidized grain and pulses to large numbers through the ration-public distribution channel. The BPL, below poverty-line people, are taking advantage of this.

They, and the working poor have been taken care of through free and highly subsidized rations available through this network; they probably will not be food-stressed, if they are daily wagers, maids, auto drivers, small tradesmen and so on. (Online direct benefit transfers to Jan Dhan accounts will help with small amounts of cash).

In this context, there is one group that has received almost no attention: those associated with Hindu temples. Since many of the workers in temples receive a pittance from the governments who run them, they generally survive on dakshina from the faithful. That source has dried up in its entirety.

Similarly, this is the season for temple festivals, and that has been entirely lost: so, for example, theyyam artists in Kerala, and the owners of elephants that take part in the festivals, are among those who will struggle to survive. Unfortunately, nobody seems to be paying any attention to these groups, who anyway live a precarious existence.

So far, there have been relatively few cases of real food distress. But that may not last if: a) all sorts of agricultural produce is not harvested, including for lack of workers, b) the supply chain is not working, c) the last mile that is the corner kirana store or vegetable stand is not open.

That last is a metaphor for the entire livelihood issue. As Professor R Vaidyanathan, formerly of IIM Bangalore, has argued, the informal sector is the real key to the Indian economy. It is likely to be affected because of a) razor-thin margins, b) lack of capital and credit, c) lack of supply.

This means ruin for some numbers of the lower middle classes, who are already shaky because of demonetization and GST (disclaimer: these are good policies, but they do hurt those from the informal economy). They who have been clawing their way out of poverty will become for all intents and purposes destitute, and join the bottom of the pyramid.

To avert this, there has to be a series of significant measures announced by the RBI and the Finance Ministry, aimed at livelihood. In some sense, it is best for the GoI to give them targeted grants as well as low-cost loans as well as a loan holiday.

Bankers confirm that instead of a loan holiday, the existing moratorium requires that the entire set of missed payments become due after three months; it would be much better to add these payments to the end of the loan with interest forgiveness so that the tenure of the loan is extended.

There are innumerable small businesses that will probably never come back to life, especially if people get used to the low-consumption regimen we have seen during the lockdown. For instance, people have done without fish and meat; without going to the movies; without driving around; without buying new clothes. Now that this is evidently possible, will it become the new normal? If so, what do you do with those turned into the permanently unemployable?

This last problem is something that must be faced by all nations, and I understand there is a movement in the US, for example, to accelerate the opening up of the economy as a prelude to a return to normalcy. But is it the old normal or some new normal? We don’t really know. Even Singapore and Japan, which had come through with flying colors in the earlier round, now face a new wave of infections and are forced to declare emergency shutdowns.

There will also be plenty of questions and recriminations in hindsight. Did Modi’s lockdown cause the Indian economy to fall apart? Did Trump’s alleged callousness cause the large number of fatalities in the US? Who knows? The fact is that the Wuhan Coronavirus (Covid-19) is one of those unforeseen things that has upset many cozy calculations.

Statistician and public intellectual Nassim Nicholas Taleb warned us early on in a one-page paper that there were so many unknowns about this virus that it’d be prudent to take extraordinary steps, even over-react. Maybe PM Modi erred on the side of caution, and made a reasonable decision under uncertainty given the data on hand at the time.

1550 words, 19 April 2020