Intimations of mortality: Ikiru and Amour at the IFFK 2012, Trivandrum

A version of the following was published by rediff.com in two pieces:

http://www.rediff.com/movies/slide-show/slide-show-1-kerala-film-fest-amour-ikuru/20121226.htm and

http://www.rediff.com/movies/slide-show/slide-show-1-kerala-film-fest-amour-ikuru/20121226.htm#1

Meditations on mortality: two brilliant films at the IFFK 2012

Rajeev Srinivasan on how two great films handle the delicate issue of death

The International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), 17th edition, concluded recently in Trivandrum cementing its reputation as India’s best film fest, especially in showcasing world cinema, both contemporary and retrospective. For instance, there were selections from the works of the Japanese master, Akira Kurosawa, and from the French New Wave’s Alain Resnais. In addition, there were many recent films, including those honored at Cannes, Berlin and other festivals.

Among the many good films on offer, I felt that two absolutely stood out, and both were on a theme that gets little attention: old age and impending death. Understandably, these are gloomy thoughts and do not lend themselves to entertainment, but these two films prove that in the hands of a master filmmaker, they can lead to great cinema.

The first is a masterpiece from Kurusowa, Ikiru, from way back in 1952. The other is Amour, by Austrian director Michael Haneke, and it won the best film award or Palme d’Or at Cannes 2012. Separated thus by sixty years, they speak about the universal issue of confronting one’s own mortality.

Ikiru (To live), in black and white and set in the bleak atmosphere of post-war Japan, is the story of a bureaucrat in the Kafkaesque City Hall in Tokyo. He has spent his entire life in meaningless paper-pushing; and then he is confronted with the intimations of his own mortality in the form of stomach cancer. He realizes he has less than a year to live, and he is forced to re-examine his life, and what he will do with that short time.

The British scholar Samuel Johnson once said that the prospect of imminent death concentrates the mind wonderfully, and that is precisely what happens to Kanji Watanabe, the bureaucrat. He is forced to re-examine his life and what he has done with it. A widower, he did not remarry because he wanted to dedicate himself to his only son. The son, Mitsuo, and his wife, Katzue, live with Watanabe in a fairly comfortable Tokyo home. But they have no use for the old man.

In a heart-breakingly poignant scene, Watanabe starts up the stairs when he hears Mitsuo calling out to him, expecting perhaps to have a chat about his illness. But he stops short when he realizes it is only a casual order by Mitsuo to lock the door. Remembering scenes from his son’s life -- him playing baseball, him in a hospital gurney waiting for an appendectomy as a teenager, him on a train going off to war as a young soldier – he repeats his son’s name, softly, “Mitsuo, Mitsuo”. But even at this time of his greatest sorrow, he is unable to relate to his son, or even to let him know of his illness, mostly because the son is absorbed in his own life and barely acknowledges the very existence of his father.

There are several big truths here that Kurosawa is bringing to our attention, especially those of us in India witnessing major transitions, just as post-war Japan changed under the American occupation. The traditional Indian family, known for its willingness to sacrifice all for the children, is now under threat as society becomes atomized. As the American model of rootless urban individualism becomes the norm, Indians should heed Kurosawa’s salutary warning about not expecting much from one’s children. The cruelty of the young should not be underestimated.

In that sense of the crumbling family and changing social structures, and also in terms of the multiple narratives (as we shall see later), Ikiru reminded me of the American Nobel-Prize winner William Faulker in two of his master-works, Absalom, Absalom! and The Sound and the Fury. Kurosawa’s complex screenplay is as rich as Faulkner’s many-layered prose.

Kanji Watanabe looks back on his wasted life – thirty years surrounded by piles of paper, the lost chance to have a wife and companion in his old age, a son to whom he is an object of derision – and wonders where he went wrong. In something reminiscent of both concentration-camp survivor Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning and mythologist Joseph Campbell’s idea of the “hero’s journey”, Watanabe embarks on a journey of rediscovery.

His first guide is the consciously Mephistophelian novelist whom he meets in a bar. The novelist, a Bohemian, takes the quiet bureaucrat on a tour through a world that is both nightmarish and appealing – that of nightclubs, ladies of the evening, jazz music – and which he is, ultimately, repelled by. No, this debauchery is not what he needs to spend the last few months of his life on.

Later, he meets a young subordinate, and her youth and devil-may-care-ness fascinate (shades of Bhuvan Shome). She tells him she’s resigning her job at City Hall, because it is destroying her soul – she tells Watanabe that she secretly named him “the Mummy”. She intends to do something with her life: she likes making things. And that gives Watanabe an idea: he needs to make something happen.

That brings an end to the first half of the film, with the stark statement that Kanji Watanabe died, six months later, of cancer. Then comes the distinctly different second half, in which his colleagues in the bureaucracy gather at his home for a funeral wake. As they get increasingly drunk on his son’s sake, we see Watanabe through the eyes of his colleagues, and their memories of him. Flashbacks, as it were, illuminate the man in Kurosawa’s masterful hands.

The interplay of memory and reality is one of Kurosawa’s signature motifs – the telling of stories from different perspectives, none of which is complete, and none of which is wrong, but the sum total of them may be a new insight altogether. As in the classic Rashomon (which, along with Kagemusha and now Ikiru are my favorite Kurosawa films), the narratives tend to be self-serving, and show us the shadow-land between objective and subjective reality.

There is a children’s park, which we understood Watanabe went to great trouble to create in a marginal piece of land under a freeway bridge. This had been a place with a stagnant pool of water, spreading disease. In his earlier life, Watanabe had stone-walled doing anything about it, sending the petitioners scurrying from department to department on a futile wild-goose-chase, in typical bureaucrat style.

But we hear from his colleagues how methodically Watanabe proceeded to defeat the red tape to ensure the building of the park. Even though the preening deputy mayor attempts to take credit, as his incredulous colleagues relate, Watanabe had spent much time and effort to ensure that the park would come up – even in the face of death threats (ironic, considering he is about to die anyway) from yakuza gangsters who want that plot of land.

We see Watanabe finally getting his wish: the park is opened, and he is seen, slowly rocking on a child’s swing in the snow, softly signing his favorite ballad about how life is short, exhorting listeners to not waste the bloom of their youth. He dies, freezing to death on the swing.

I am used to Kurosawa’s epic samurai films, full of war, grand battle scenes, violence and heroism in glorious color, including his Shakespearean Ran. This film is completely different: instead of his favorite leading man, the dashing Toshiro Mifune, the hero here is, as befits the film, the gravely-voiced, dour salaryman played by the understated Takashi Shimura: but he is a hero, nonetheless. And it is one of the best explorations of death I have ever seen.

================== PART II =====================

Micheal Haneke is a good contemporary director, but I had a poor opinion of him based on a previous film, White Rabbit, which also won a Palme d’or at Cannes (2009), but which I found completely unwatchable. The standing-room audience at the IFFK 2009 felt the same, and melted away in boredom as the film progressed.

But Amour is a different matter altogether. It is a simple story of two 80-year-old music teachers growing old together in a comfortable apartment in Paris. They have had fulfilling lives; apart from worries about their musician daughter (played by the beautiful Isabelle Huppert) and her loathsome, philandering British husband, there is little amiss in their lives. They proudly go to concerts by their protégés.

Then, one day, something happens. Georges notices that Ann has simply gone blank for a noticeable amount of time: she doesn’t react at all. And she has no recollection of this happening. From this small beginning, Ann’s health goes downhill rapidly. She has apparently had a stroke. An operation to correct the effects is botched, and she is left partially paralyzed down the right side of her body. But that does not affect her self-possession: she adjusts, but she begs Georges to not send her back to the hospital.

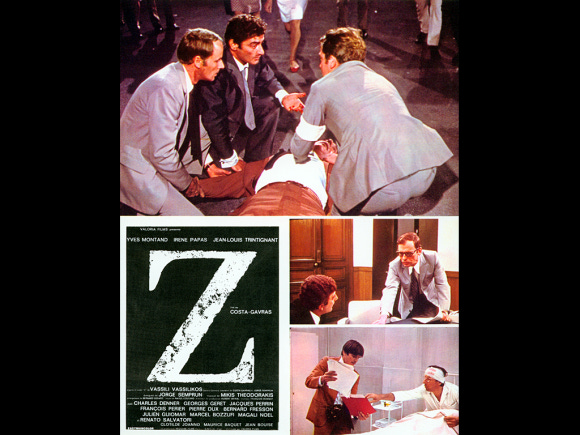

It is worth noting that the main actors are acknowledged greats. Georges is played by Jean-Louis Trintignant, who won the Cannes 1962 Best Actor award for his remarkable portrait of the stern investigating magistrate in Costa-Gavras’ Z (He Lives), arguably the greatest political film of all time. Ann is played by Emmanuelle Riva, whose role as the unnamed Frenchwoman was the highlight of the brilliant Hiroshima Mon Amour (1952), also concerned about memory and forgetting, which, by a happy coincidence, was also at the IFFK 2012 as part of the Alain Resnais retrospective.

Amour, which starts gently, then becomes a harrowing tale of Ann’s terrifyingly rapid descent into dementia. Before his very eyes, Georges sees the woman he loves turn into a cripple first, and then, after another stroke, into a semi-conscious vegetable, practically in a coma. She deteriorates: at first, she is merely wheelchair-bound. But despite her apparently cheerful acceptance of her paralysis, he can see her anger and helplessness in a telling scene: she races her electric wheelchair up and down the small room, wheels it around, in what appears to be blind, impotent rage at her condition.

For a while, Ann is manageable. But with her next stroke, she begins to regress. She becomes like a child, unable to articulate coherent sentences. She blabbers, she is incontinent, she will not eat, she throws tantrums and refuses to swallow the water he is feeding her. She keeps moaning apparently in pain, but as the home nurse explains matter-of-factly, she isn’t trying to say anything, it is merely a reflex. Her mind and personality are disappearing rapidly. She is like a mentally-retarded child.

This takes its toll on Georges: it is getting beyond his ability to cope. Even though his neighbors congratulate him on his willingness and ability to look after his wife on his own despite his advancing years, we see helplessness and hopelessness in his very gait. The dapper and stylish man that he is at the beginning becomes shabby, and he starts to shuffle his feet instead of walk: the body language shows the hopelessness behind the brave façade. He loses his cool, too: he slaps Ann, hard, when she refuses to co-operate, and the shock is palpable, both for her and for the audience.

There is the recurrent motif of a stray pigeon that I did not quite understand, but the film continues as a harrowing and deeply moving experience. For one, you are reminded of your own elders, who might well be in the same situation – it is not possible to depend on hired nursing care (Georges has to speak sharply to and fire a nurse for incompetence, to which she responses with profanity) either.

And going one step further, it forces you to confront your own mortality. Whatever you might be, whatever your accomplishments, one day you may end up in a semi-coma like Ann, in a situation where you may want mercy-killing, but are unable to articulate that, as your mind is far too gone. Can you depend on your loved ones to do let you live with even a shred of dignity? Can they in fact cope with the physical and emotional burden that you have become?

As in the case of the unfortunate Watanabe, can you depend on your children? Or will you be subject to the tender mercies of some brutal attendant in an old-people’s home? These are not theoretical questions, as absent, grown children (for example the legions of non-resident Keralites) have no time for their elderly paretns. And what can you do today for some aged relative whom you might find a bit of a nuisance? Should you be more kind to them, imagining yourself in their shoes?

The disappearance of a mind is shattering to watch. I was reminded of, of all things, the computer HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey, whose memory is systematically removed by the astronaut, and who regresses in front of our eyes, reduced to singing nursery rhymes. That moment of decline and loss – with HAL pleading for mercy: “Dave, my mind is going. I can feel it” -- made HAL the most human element in that film, even more so than the somewhat wooden human actors. What, after all, is a human without memories? A nothing. Maybe an imperfect computer.

Amour, thus, is not an easy film to watch. But the capacity crowd gave it a standing ovation – it is a touching film about human frailty, fraught with meaning. A critic once said that Ikiru is the one film that can make someone rethink and change their life; maybe Amour is another, a classic in the making.