This essay was published by firstpost.com.

The Hero’s Journey is a common metaphor used by storytellers from the Ramayana to the Iliad, and in innumerable modern works. You have the hero rising, then facing odds that are so overwhelming that he is on the verge of failure, but he often wins in the end, and is transformed or redeemed in the process. And indeed, for each of us, our own lives are heroes’ journeys, as the mythologist Joseph Campbell elucidated in a series of excellent documentaries.

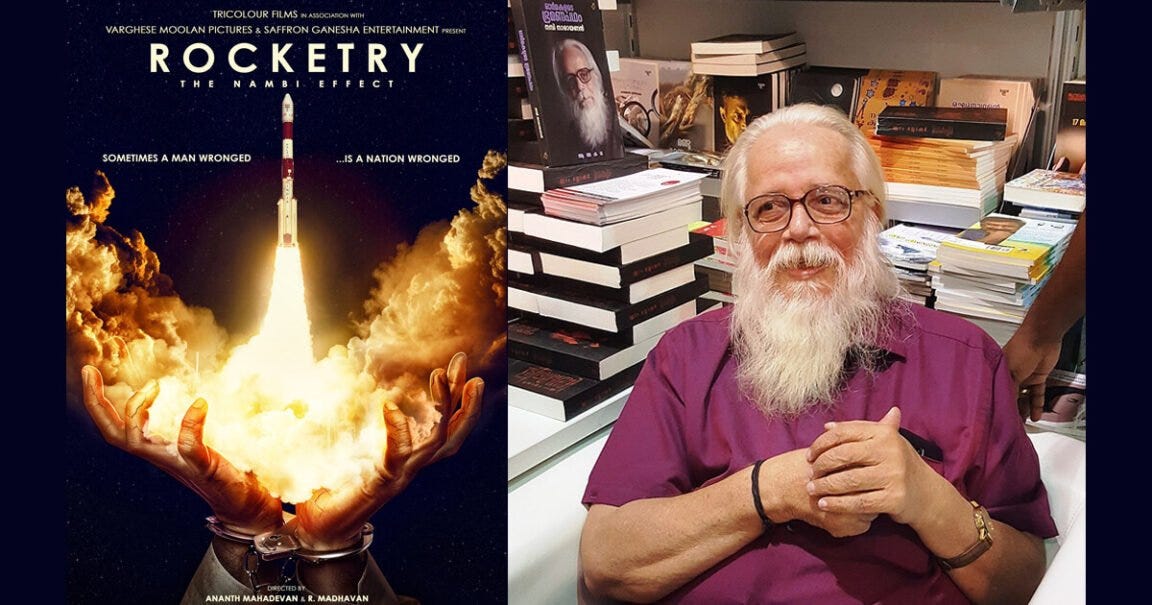

Both the recent films Kantara and Rocketry: The Nambi Effect, in my opinion, fall into this broad categorization; but what’s notable and different is that they are about very Hindu heroes, quite a departure from the standard Indian film (especially of the Urduwood variety) where overt Hindus are usually depicted with contempt or disgust.

The two films are very different from each other, of course, but it is telling that they both resonate with audiences, in a visible departure from the conventional wisdom that holds that neither a Hindu nor a nationalist should be depicted with sympathy, and especially not a Hindu nationalist.

There is another Hindu meme: the local and the national are not meaningfully distinct, just as the Atman and Brahman are not. Kantara, set in the Tulu-land of Dakshina Kannada district, Karnataka, is instantly understandable to Hindus anywhere; and Rocketry, the story of a patriot of Tamil origin living Thiruvananthapuram, who is attacked and to whom tejovadham is done by mysterious, malign forces, is understandable to any Hindu, we whose face hostility in India and elsewhere.

When I saw Kantara, I was surprised by how normal the story was to me: of course, obviously, there are spirits, or demi-gods/daivas all around. This is something that I grew up with. I remember as a small boy being taken by my grandfather to the bharani festival of the village Devi temple in central Travancore: there were wondrous, magical things there then.

Much later, I watched theyyams in Malabar, which is adjacent to Tulunadu, and the wonderful costumes are almost identical to those in the Bhoota kola depicted in the film; some of most impressive were thee-pothi (the fire-goddess) and the gulikan (the fierce deity identical to guliga in the film), especially as they performed at dusk.

The belief in possession by spirits, as in the hypnotic sarpam-thullals (serpent-dances) of Travancore or of velichapads (oracles) in many parts of Kerala, holds no surprises for me. It is easy for a practicing Hindu to believe in them. It is not hard to imagine benign (and malign) spirits all around, for example as in O V Vijayan’s story The Little Ones, luminous ancestral spirits that help in times of trouble.

I had a personal experience of the Divine, on my first trip to Sabarimala when I was a teenager. It was an incredible religious experience: for a moment, a glimpse of something extraordinary, a powerful vision of the Infinity of Grace. My friend, a doctor, tells me of medical miracles that can only be attributed to the power of prayer and Divine Grace.

In Kantara, the protagonist Siva consistently and carefully avoids the bhoota kola, as he was traumatized by the unexplained disappearance of his father, the oracular dancer of the village. He tries to lead the life of a carefree youth, drinking, hunting wild boar and getting into fights; but the panjurli daiva calls to him in his dreams. Spoiler alert: his hero’s journey culminates in a spectacular finale.

In Rocketry, the fictionalized story of the real-life Nambi Narayanan, the hero’s journey is even more evident. After early and brilliant success as a rocket engineer, his life and career were ruined in what was apparently a sordid combination of commercial sabotage by a three-letter acronym spy agency, and a power struggle among Congress politicians in Kerala, with some corrupt policemen in the mix.

Even if it is a little exaggerated for rhetorical purposes, Nambi Narayanan’s efforts to convince Rolls-Royce’s head (a Scot), the French Ariane rocket program, and the Soviet cryogenic labs to transfer technology and know-how to ISRO are amazing stories that I too had not heard, even though I live in Thiruvananthapuram, where Narayanan and Abdul Kalam did their work on solid and liquid-propelled rockets.

Despite Narayanan’s value to the Indian space program, and the evident holes in the 1994 Maldivian spy story (see my Rediff column Who killed India’s cryogenic engine?) it took a court saga of 24 years to clear his name, and to get the redemption he deserved (a Padma Bhushan in 2019). In the meantime, India’s cryogenic engine was delayed by 19 years.

What is remarkable in the film -- and it is disturbing that this should even have to be highlighted -- is that Narayanan is shown as an unapologetic Hindu. There is nothing whatsoever that prevents an observant and pious Hindu from also being an engineer and scientist: no dogma. But the prevailing filmi wisdom, which has become “truth by repeated assertion” is that Hindu rituals are superstition, but Abrahamic superstition is somehow ‘scientific’.

The very fact that such films are being made, and are becoming blockbusters, shows that the narrative is shifting (the so-called Overton window). There is pushback, though: a little-known band in Kerala is suing Kantara over the song ‘Varaha-roopam’, which has Sanskrit lyrics and traditional tribal music. Because traditional knowledge cannot be copyrighted, it is likely that their intellectual property claim is not sustainable.

There were also people grumbling that Narayanan was lionized and that he wasn’t as key to ISRO’s success as the film makes him out to be. Maybe, but even if it was 50% exaggerated, he is still an amazing engineer and manager, and in any case it was unconscionable by any measure to torture him for 50 days, defame him, and destroy his career. Those who ordered the hit have never been named.

My heroes have long been those among us who fight for Dharma and righteousness: Professor Eachara Warrier, Major Shaitan Singh. I am happy to now add Dr Nambi Narayanan to that list, and perhaps Siva, who brings to life the forest deities.

1020 words, 3 Nov 2022

Share this post