This long-read essay was published by swarajyamag.com at Is Industrial Policy The Right Answer For India?

Should India have an Industrial Policy? Reasonable people can honestly differ on this question. There are several sub-questions: Does India have the State (and labor force) capacity to come up with, and deliver on, such a policy? What has been the experience in other countries, and indeed in India, when there was implicit or explicit policy in place?

Perhaps more fundamentally, is manufacturing important, or should India jump straight into services? Does India need an explicit Industrial Policy that identifies strategic industries and picks winners and losers, or is it enough to put in place regulatory, antitrust and related mechanisms to provide gentle guidance? What about incentivizing R&D and radical innovation? How can taxation be made a tool of Industrial Policy if not also used for social justice?

In the wake of the recently introduced Production Linked Incentives in various sectors, and the immense efforts being made to jump-start the semiconductor ecosystem, these questions take on some urgency. There are a number of factors, including the putative ‘demographic dividend’, and the fact that India is in the $2000+ GDP per capita range, which is often a takeoff stage.

Industrial Policy now has another driving force: national security, from at least two perspectives. The first is that India was for quite some time the world’s biggest buyer of defense equipment. It is a huge risk because of potential embargos. Second, it is clear that depending on others for crucial components can be potentially disastrous: remember US technology denials in supercomputing, and cryogenic engines, as well as China’s sudden decision to deny Japan rare earths supplies.

But there are some downsides too. India’s earlier flirtation with State-guided growth, as in the Five Year Plans, ended up in the debacles of the License-Permit Raj, large-scale nationalization, and a ‘hybrid economy’ which was the worst of both worlds, capitalist and socialist. More recently, the ‘Make in India’ lion mascot has been quietly shelved, and despite Atmanirbhar Bharat, our trade deficit with China continues to soar.

The ghosts of the mai-baap sarkar and the ample mammaries of the welfare state continue to loom over India. Just a week ago, aspiring railway employees set fire to trains out of general frustration: it is reported that 1,25,00,000 people applied for 35,281 positions. The attractions are obvious: government jobs mean no accountability, no performance reviews, no chance of dismissal, plus baksheesh and pensions. This breeds mediocrity, as in the Soviet Union.

Is Manufacturing Important?

In a word, yes. Indians dazzled by the success of the IT services industry may not agree, and to give credit where it is due, it has provided decent jobs and created wealth (in many cases, extraordinary wealth) for a lot of individuals, but it is still a drop in the bucket. According to Association for Computing Machinery cacm.acm.org there is a total of 4 million direct and 12 million indirect jobs in IT, but that doesn’t begin to address the problem of providing jobs to the perhaps 10 million young people entering the workforce every year, often with a poor education that has taught them no skills.

Besides, manufacturing cannot be seen merely as a provider of jobs for the teeming masses: its effects persist. It may have a critical role in the creation of dynamic competencies that enable a nation to be resilient to changes in the industrial and trade environment. It is well-known that entire industries do have a lifecycle S-curve, wherein they rise, plateau, and despite possible mid-life kickers, they eventually decline. The physical and financial infrastructure, the supply chain linkages, and cluster effects, however, have lasting value: see how, for instance, Silicon Valley has weathered several waves of disruption and may yet recover from the latest.

In 2004, Dani Rodrik at Harvard wrote an influential paper titled Industrial Policy for the 21st Century. But these ideas are not new. In a seminal paper from 1986 in Research Policy titled Profiting from Technological Innovation: Implications for Integration, Collaboration, Licensing, and Public Policy, the Berkeley economist David Teece provided a grim warning against deprecating manufacturing:

… Put differently, the notion that the United States can adopt a “designer role” in international commerce, while letting independent firms in other countries such as Japan, Korea, Taiwan or Mexico do the manufacturing, is unlikely to be viable as a long-run strategy.

Teece was prophetic, as China has demonstrated by de-industrializing the US. This explains America’s huge and growing trade deficit with China, and the US is hanging on largely because of the fact that the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency. If and when that changes, the US economy will be in trouble.

India, in semiconductors for example, is justifiably proud of its design talent, but that is a moveable feast as the designers can move anywhere, to any geography. They are footloose, and in any case, design is only a part of the value chain (albeit a very important one). On the ground capital investments, which amount to up to $20 billion, are not so easy to transport.

Indians need look no further than the recent pandemic to see the truth of Teece’s emphasis on manufacturing. Without the existing capacity for scaling up vaccine production, India would have been left in the lurch. The 1.5 billion vaccination landmark is entirely the result of having implicit manufacturing know-how and supply chains. Even more impressively, Bharat Biotech’s success at inventing and bringing Covaxin to market is the very kind of R&D and innovation success story that manufacturing brings.

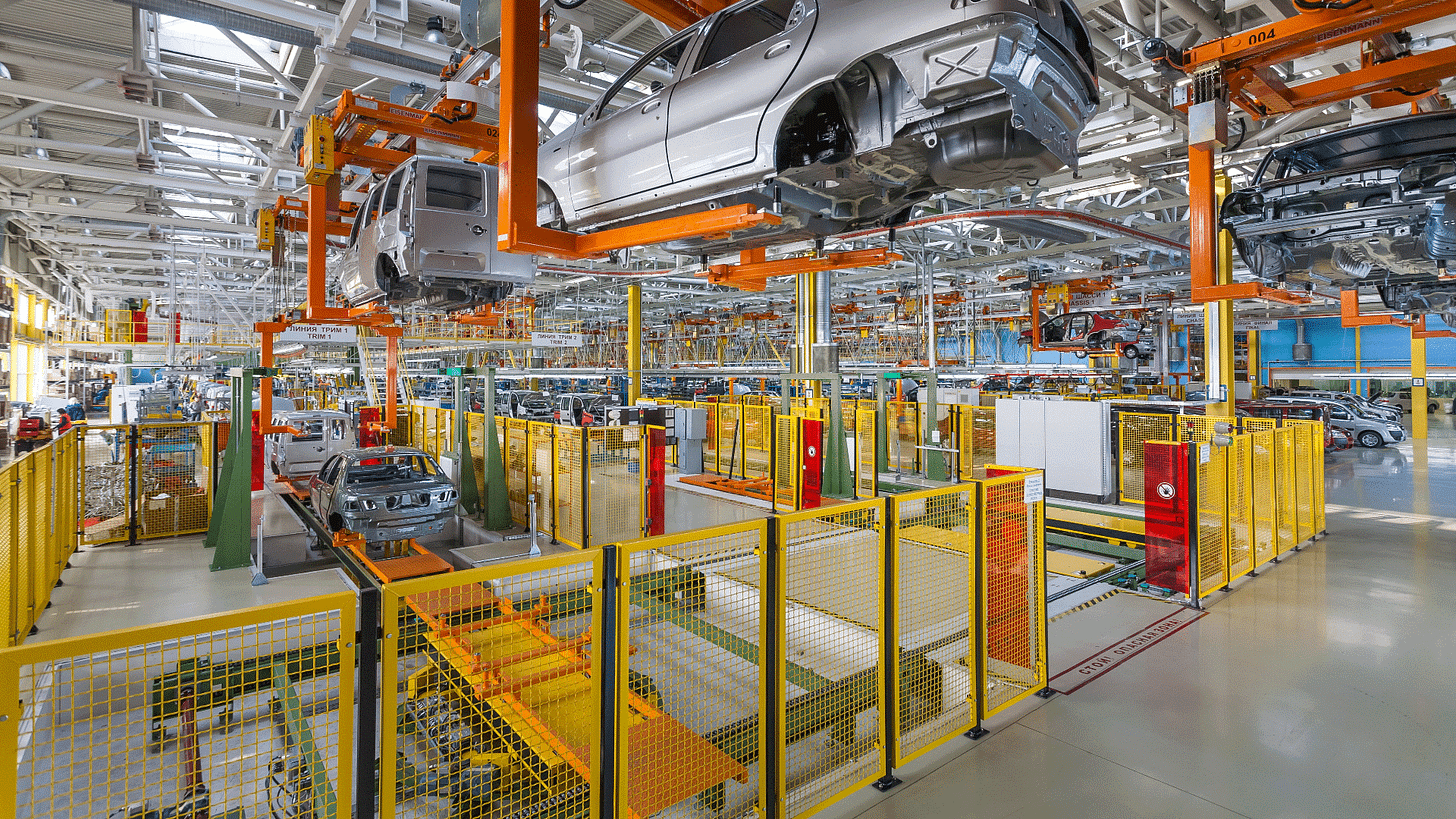

The Economic Survey 2022 also points to this factor: manufacturing has recovered faster than services post-pandemic. That is possibly because many services are optional: vacations, dining out, even haircuts can be postponed; yes, non-essential big-ticket purchases of manufactured goods like cars can also be postponed. But on average, manufactured goods, as well as agriculture (well, you have to eat even in a pandemic) appear more ‘sticky’ in terms of sustained demand. Remarkably, it is the public sector that has supported services demand, especially defense related spending and I imagine healthcare spending (all those vaccines).

Fads, fashions and duality in business models

The world of business is apparently as prone to fads as the fashion industry itself. We know how, in the latter, what we today think of as quaint curiosities as 1970s bell-bottoms will reappear eventually as the very height of a la mode fashion. Similarly, fads in trade and industry (or at the very least, tendencies) have a way of showing up again eventually.

There are probably good explanations for this recidivistic behavior. One possibility is that there are multiple reasonable and viable business models that vie for acceptance; once one of them becomes dominant, then we inevitably see the flaws and excesses in that model. There is a backlash, and the charms of the alternative model become ever-more seductive, and eventually there is a wholesale switch to that model. And then it is rinse, repeat.

It is also possible that the Universe is fundamentally a steady-state entity, one that doesn’t lend itself to linear models of ever-greater progress. It may be cyclical, as there may not be one right answer to the problem, so that we oscillate between two different models. That is pretty much what we are seeing in business and industry all the time: a model succeeds for a while, but then the pendulum slowly swings back to the alternative.

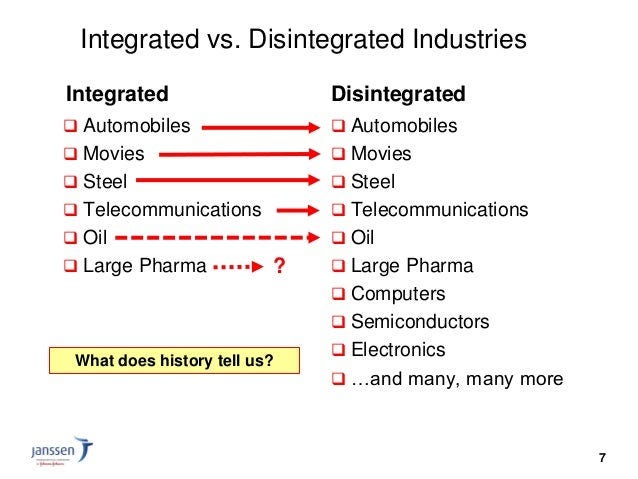

A good example I have observed is the tension between an integrated and a disintegrated model in the computing industry. In the early days of computing, the integrated IBM model was dominant, where IBM provided everything lock stock and barrel: hardware, software, peripherals, consulting.

It worked for a while, but in the second phase of computing, it was the disintegrated Wintel model that succeeded, with Intel and Microsoft providing the core technologies, but a veritable army of partners offering a plethora of solutions.

That seemed to be the obvious solution, and the ecosystem thrived, although many OEMs such as HP, Dell, Toshiba etc made only tiny profits, as the vast majority of the margins were sucked up by the Intellectual Property holders, mostly Intel and Microsoft.

It was into this world that Apple iPhones arrived with a fully integrated model (especially control of the user experience): chips designed by Apple, software made by Apple, hardware assembled by Apple, with the only open part being the third-party software catalog (though even here Apple charged/charges a hefty 30% fee). This has succeeded wildly, making Apple by far the most valuable company in history with a market capitalization of $3 trillion.

It is a fair bet that the next phase of computing will be another pendulum shift to disintegration as the Apple model runs out of steam. Let us note that even though it gushes cash, there have been no exciting new products from Apple for years.

end of Part 1

Ep. 58: Is Industrial Policy the right answer for India? Part 1